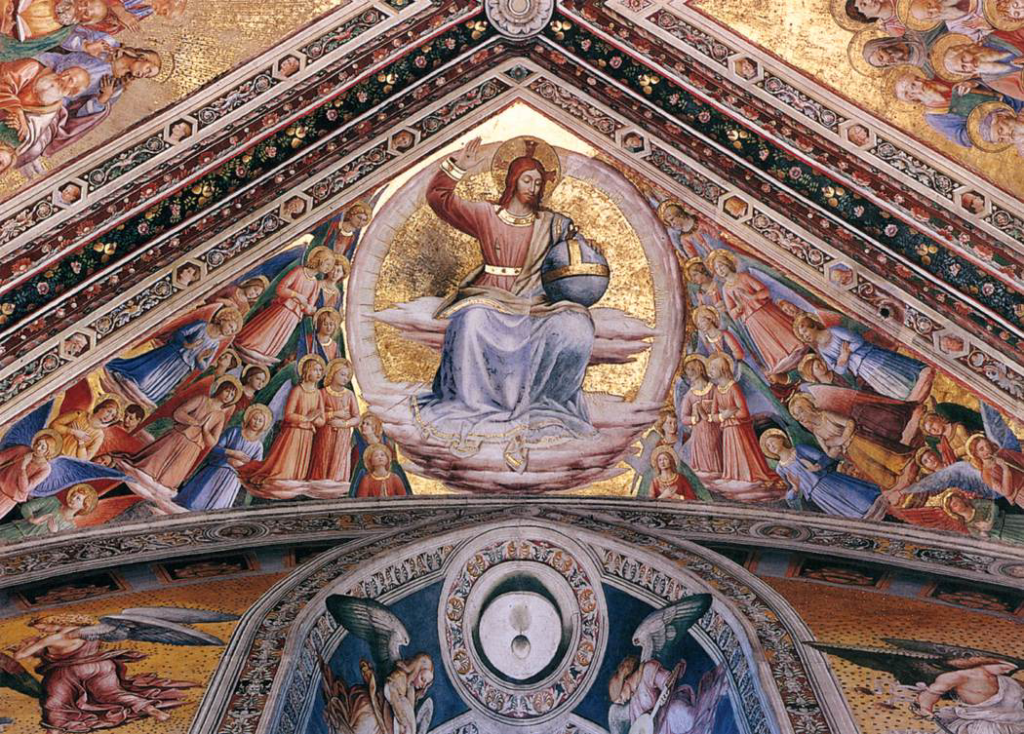

Image of the “Christ the Judge” fresco painted by Fra Angelico in the Chapel of San Brizio, Duomo, Orvieto taken from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fra_Angelico_-_Christ_the_Judge_-_WGA00679.jpg.

“The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either — but right through every human heart.”

– The Gulag Archipelago, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

“In that day the root of Jesse, who shall stand as a signal for the peoples—of him shall the nations inquire, and his resting place shall be glorious” (Isaiah 11:10).

For most of us, in terms of our religious awareness, the relationship between “Jew” and “Gentile” is a non-problem. For some of us, the “problem” is one of the past, solved once upon a time by juvenile Christianity trying to sort through the mirky relationship between itself and its parentage. For very few of us is the question of this relationship an internal feature of how we understand our own situation. That makes a lot of the New Testament hard to understand (or, rather harder to understand, because it’s already hard to understand). At the very least least, it makes it harder to understand how it matters for us. I suspect this is the case because we tend to think of our relationship to God outside of the context of his mission.

The division between “Jew” and “Gentile” (from the Latin word gens, meaning “family or nation,” which the Latin Vulgate uses to translate the Hebrew word gôy, which we often translate as “Gentile”) was created by God, but identified in relation to Abraham, the first “patriarch” (of three, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob). God elected Abraham and commanded him to go out from his homeland (he “churched” him). He promised that Abraham’s descendants would become a “great nation” (Genesis 12:2). However, this wasn’t God’s intervention on behalf of someone he arbitrarily preferred (see Acts 10:34; Romans 2:11). Rather, God promised to exalt Abraham so that, in him, “all the families of the earth shall be blessed” (Genesis 12:3; compare Genesis 22:18 and Galatians 3:15-29). Inherent in the election and exaltation of Abraham was the blessing of “the nations.” In itself, the division between Jew and Gentile (although all-encompassing) is an effect and not really the point, not the goal of God’s promise. However, it’s an effect that plays a significant role in God’s mission. To the Israelites, as Paul writes, “belong the adoption, the glory, the covenants, the giving of the law, the worship, and the promises. To them belong the patriarchs, and from their race, according to the flesh, is the Christ” (Romans 9:4). Despite its very real significance, it remains not-the-point. But for many the effect became the point. Into this situation, a division seen one way or another as an absolute line of demarcation between “us” and ”them,” Christ comes.

With untamed fury and uncompromising resolve, John the Baptist begins his preaching ministry, his forerunning, telling the Pharisees and Sadducees that their relation to Abraham could not substitute for “fruit in keeping with repentance” (Matthew 3:8), because “God is able from these stones to raise up children for Abraham” (Matthew 3:9; no less than this was Abraham’s calling God’s prerogative). John promised and forewarned that one was coming after him with “the Holy Spirit and fire,” who would “clear his threshing floor and gather his wheat into the barn, but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire” (Matthew 3:11-12).

The approach of Christ appears as judgment and blessing, in order to fulfill the Law and the Prophets (Matthew 5:17), for “he has broken down in his flesh the dividing wall of hostility” (Ephesians 2:14) by confirming (not changing) “the promises given to the patriarchs” (Romans 15:8). Christ comes as the heart of the Law to judge its subjects. His pronouncement is the gravitational center of the world, around which all creation, stripped of power and frenzy, gathers to listen (Isaiah 11:6-9). His word is water which quenches the earth’s thirst, giving rise to life and plenty (Psalm 72:6-7). The mission of God is to accomplish the coming of Christ, whose figure casts the shadow of the Law and the Prophets (Colossians 2:17; Hebrews 10:1), the covenants of promise and the election of the patriarchs, including within this the division between Jew and Gentile. In his figure, though, “the Gentiles are fellow heirs, members of the same body, and partakers of the promise in Christ Jesus through the gospel” (Ephesians 3:6).

Today, I commend a question for self-reflection: How can you acclimate to God’s mission, to what God’s doing in the world? In the birth of Jesus, God reveals the inclusion (already there, not appended!) of all the nations in his mission (see Luke 2:25-32). He also undoes the false securities of “God’s people.” God’s tools had become points of pride for his people. We too must be alert to this danger. The birth of Jesus isn’t a stylistic knick-knack or a feature of our common culture—and life as his people isn’t a social club, a way to make new friends, or a way to fill some need we have. Rather, in the “Yes” of God (2 Corinthians 1:20; “yes” to his promises, not to our projects), there is necessarily entailed the “No” of God. When the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand, we must repent.

Further Reading: Psalm 72:1-7; Isaiah 11:1-10; Romans 15:4-13; Matthew 3:1-12

Written by Guest House Theologian, Tim Morgan. These reflections are a complimentary addition to our Advent Coffee Bags.

More Advent reflections can be found here.